It’s hard to believe it’s already been more than 4 years since I graduated college. Harder still that I’ve managed to keep track of the notes I made on my university senior design project, a three wheeled vehicle chassis designed from scratch for the solar car team.

This was a pretty ambitious project. Over the course of a year, myself and three other mechanical engineering students designed and fabricated a complete race car chassis including the frame, suspension, hubs, spindles, brakes, & steering.

In retrospect any one of the above systems would have been an adequate senior design project. The decision to attempt all of them together reveals the ignorance/arrogance/ambition of my younger self. Fortunately, we were successful in the end. And I know I learned a heck of a lot about chassis design and what a handful of exhausted engineers can do in a short period of time.

More pictures & detailed design instructables here.

For EngineerDog readers I wanted to share my favorite section of the instructable, a unique perspective on three wheel vehicle dynamics: My answer to the question, what are the advantages/disadvantages of having two wheels in the front instead of the back on a three wheeled vehicle?

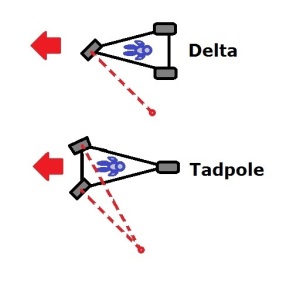

To answer this, we need to first define the two different vehicle layouts and compare them for a few different vehicle performance characteristics:

Delta: One wheel in front, two in back.

Tadpole: Two wheels in front, one in back.

Dynamic Stability: When a vehicle is said to be dynamically stable it is meant that it reacts safely and predictably under various driving conditions.

When designing a chassis, we can choose how the car will react when turning too fast. One of two things will always happen: either the car wheels will slip relative to the ground, or the vehicle will tip over. Obviously, slipping is the preferred outcome. Keep this in mind for the moment.

When the car does slip out of control on a fast turn, we can design it in such a way that we know whether the front or rear wheels will slip first. This is important because if the rear wheels slip first, the vehicle runs the risk of spinning out of control (oversteer).

If the front wheels slip first (understeer), you won’t spin out and it is easier to regain control. Understeer is considered a safe dynamic response to slipping in a turn and is designed into all commercial cars. Which wheels will slip first is a function of weight distribution and weight transfer during turns.

The problem for delta vehicles is how to distribute their weight and control their weight transfer during a turn to avoid undesirable outcomes. If you design the weight distribution for a heavy front bias to achieve understeer, you increase the risk of tipping over. Alternatively, if you increase the weight distribution on the rear tires, the vehicle will oversteer in hard turns, also bad.

We also need to consider ‘nose diving’. That is, when you slam on the brakes as hard as possible, the vehicle will either skid to a halt or the rear wheels will lift off the ground. This is also a function of weight distribution and weight transfer. It would seem that the delta design has an advantage here because it naturally lends itself to having a rear biased weight distribution. But in the real world, a hard stop doesn’t always occur when traveling in a straight line.

If you stop hard enough while turning with a delta vehicle, the weight will transfer to the front wheel enough to cause the vehicle to flip over at an angle. See the first ten seconds of this Reliant Robin car test drive video.

Category Winner: Tadpole

.

Braking: Because your weight transfers to the front when you decelerate, the front wheels on any vehicle provide the majority of your stopping power (something like 60-70%). The delta is at a disadvantage considering the weight distribution issues discussed above and the fact that it has one less front tire to brake on. Category Winner: Tadpole

.

Simplicity of Design: Steering is definitely easier to design for the delta. No special considerations need to be taken into account to avoid lateral wheel slipping on turns, while the tadpole design has to incorporate extra linkages to approximate ‘Ackermann’ steering geometry to prevent wheel slippage.

Front suspension design is definitely easier on the delta. The best choice is a ‘telescopic fork’ positioned with some degree of caster angle to ensure that the car drives straight when you let go of the wheel. (Setup like a motorcycle). The rear suspension design can be any number of options.

The reverse is true of the tadpole. Multiple choices are available for the front suspension, while the rear suspension is much easier to design (a ‘swing arm’ being the obvious choice). Imagine designing a toy tricycle for a child. Have you ever even seen a tadpole design like that? Category Winner: Delta

.

Aerodynamics: The tadpole design lends itself better to the aerodynamic tear drop with the correct length/width ratio (.255) more easily than the delta. The image below shows how poorly the correct shape fits the delta design. Plus, you have to encase more empty space with the delta.

Category Winner: Tadpole

Powertrain: The delta design has more disadvantages when selecting your drive wheel. If you go with front wheel drive, you have to fight against the dynamic stability disincentive of putting too much weight on the front of a delta. You also have to make sure that your steering system doesn’t conflict with your method of driving that wheel.

If you power a back wheel on a delta you need to add a differential gear to the rear wheels or else risk stability issues caused by the off center driving wheel force. (Exampled below on a 4 wheel vehicle footprint).

On the other hand a tadpole with rear wheel drive gets the best of both worlds. No differential is necessary and you can keep a good 30% of the vehicle weight on the drive wheel to maintain traction. Category Winner: Tadpole

.

Conclusion: For most vehicles the tadpole is clearly the best option on three wheels. However, the delta will always have value for niche applications.

.

PS: If you enjoyed reading this and missed the link to the Instructables, you’ll definitely want to check that out here. Its a 15 step guide that goes into even more detail about each step of the process of building this chassis.

For those interested in further reading about solar cars or race car design I’ve put together a list of the books I used to figure all this stuff out. None of this would have been possible without these resources.

Recommended Books:

have driven a few tadpoles and risked my life on a few deltas. Your tadpole looks like a great time

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hah thanks! Did you used to own one of those ATV 3 wheelers? Those things were notorious for flipping over. Other than those you don’t see a lot of deltas out there.

LikeLike

I have driven a few tadpoles and risked my life on a few deltas. Your tadpole looks like alot of fun, when can we see the youtube video

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve got a video of just the suspension components articulating here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ytlqz0r5vYQ

And there is another video of the car after later students built the body, panels, batteries, etc, here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4A4Fwh9GFhU

LikeLike

[…] of soliciting donations from alumni. Last week I got the call and after a brief discussion about solar cars and my discomfort at the mere thought of parting with money, the student asked me a final survey […]

LikeLike

we are trying to make self driving car i am not understanding how to do odometry calculation for tadpole design

LikeLike

The old JAP & Matchless Morgan three wheelers have always been the safest. They are Tadpoles and that says enough for me. I even knew a couple of people some years ago with Morgan F2’s who doubled up the rear wheel so they are 0nly 9″ apart, by making up their own rear sprung sub-frames. They still drive just one wheel so technically while having 4 they are still configured as a 3 wheeler and provide extra safety in added stability.

LikeLike

I had a neighbor who was a motorcycle enthusiast, he told me he built a delta three wheel motorcycle once. He told me that the engine was in the rear, and when he drove it and came to a corner, the vehicle would not make the turn, it just went straight right off the road. There was not enough weight on the one front tire. So he put the engine in front and the vehicle drove just fine. However General Motors designed and built a three wheel delta, the XP-511. In Jan P. Norbye’s book: “Car Design Structure and Architecture” this is what was said about the car: “The three wheel layout-one in front, two in rear-provided excellent stability and maneuverability. It reduced weight, simplified the steering and allowed for an uncomplicated “backbone” type of frame. The low center of gravity, only 13 1/2 inches off the ground, offered exceptional lateral stability and cornering capability.” And the engine in this car was in the rear! It seems to me that if a delta style three wheel car is designed correctly, it will make an excellent vehicle.

LikeLike

because all of the roll stiffness is at the pair of wheels,most of the mass should be near the pair of wheels, ideally even with full passenger and fuel load. My rule of thumb is 76% of the weight on the pair of wheels. It follows that the pair of wheels should be the ones powered. The Delta is the most stable platform dynamically.

With 24% of the weight on the front, it will turn quite willingly, and can be driven aggressively out of a corner.

Delta or tadpole configurations with the same relative CG locations will corner at a steady state at the same speed.

See Three-wheel Passenger Vehicle Stability and Handling NHTSA Paper #820140 by Paul van Valkenburgh and Richard Klein.

The argument that tadpoles may be more aerodynamic was made, but Delta configurations can make downforce with reduced drag.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi! Do you have a mechanical drawing of this? Thanks!

LikeLike

If I keep drive at rear in Tadpole, how would be the stability of the vehicle?, And as same way if I go for front drive in Tadpole, I have to use a differential unit.

So please suggest me what would be the optimum track width , that I can consider for front drive in tadpole to avoid differential unit.

LikeLike

Here in the U.S. we had perhaps the most famous tadpole of them all, the Dymaxion car designed by Buckminster Fuller. Ironically, it never went into production.

LikeLike